I have a challenge for you readers. Name two psychologists/cognitive scientists whose research has impacted education in the past twenty years.

Were you able to?

Perhaps that was too easy. New challenge! Name two psychologists/cognitive scientists who have published impactful work in the past twenty years AND were also featured at a workshop or PD session that you attended.

Harder?

I (Zach) would be surprised if you were able to answer either of those questions quickly, or even at all. It seems like most teachers can name-drop Piaget, or Vygotsky and his zone of proximal development, but little else more recent. Include them with Pavolv and his dog and Skinner and his operant conditioning and I’d say that we’re starting to get near to the extent of what we teachers are expected to know in terms of educational psychology. I can speak from experience that it wasn’t until fairly recently that I started to learn any cognitive science that went beyond the Psychology 101 textbook.

I want to question in this post why teachers seem to know so little about basic learning science. Given concerns about the apparent gap between education research and teacher practice (Vanderlinde & van Braak, 2010) and the pervasiveness of so many myths in education (Macdonald et al., 2017), I think it is time we went beyond memorizing cursory knowledge about influential – but outdated – figures like Piaget and Vygotsky and into a new era of teacher education that prioritizes the rigorous learning of cognitive science, with a particular focus on current developments.

What should teachers know?

This post is certainly not an anti-Piagetian, anti-Vygotskian rant. In fact, if you look back over most of the posts Stephanie and I have written on this blog, you’ll probably find a mostly sympathetic view towards their body of work. It’s just that, well, their ideas are now pretty old; Piaget’s The Origins of Intelligence went to press in 1952 and Vygotsky’s Thought and Language in 1962; and they seem to be the two figures that are given the most airtime at staff meetings and PD sessions. Much of their seminal work has since been challenged, modified, or abandoned altogether and replaced with new explanations. And indeed, as Willingham (2018) mentions, most psychology textbooks feature lengthy descriptions explaining ways that many of the 20th century contributions to cognitive science are now inadequate.

Take Piaget’s stage theory, for example. We now have enough empirical data that contradicts Piaget’s observations that humans develop in a succession of discontinuous stages. Nowadays, most cognitive scientists view development as a gradual, continuous process (Martinez, 2010). As one of my textbooks explains:

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development stages was a monumental achievement and a tremendous contribution to twentieth-century psychology. Nevertheless, all theoretical advances are subject to testing, critique, and, indeed, attack from other quarters. Competition among ideas helps to ensure that the theories psychologists construct are of high quality. It is not surprising, therefore, that the ideas of Jean Piaget were spared no criticism. And when put to the test, some of the central proposals of Piagetian theory did not hold up to scrutiny (Martinez, 2010, p. 204).

It’s not as if information like this is not out there for teachers to find; It’s become common knowledge in some circles, just not in ours! The American Psychological Association, for example, explicitly recommends against using stage theory to inform instructional decisions in one of their Top 20 principles of PreK-12 teaching and learning:

“Students’ cognitive development and learning are not limited by general stages of development […] Student reasoning is not limited or determined by an underlying cognitive stage of development linked to an age or a grade level. Instead, newer research on cognitive development has supplanted these stage theory accounts” (2015, p. 9).

If teachers had long ago moved towards designing instruction that embraced the current best practice – assessing and building upon children’s’ background knowledge and presenting topics in intellectually honest ways, regardless of age or “stage” (American Psychological Association, 2015) – we wouldn’t hear so often the phrase “well, that’s not developmentally appropriate for this grade” and there’d be no need to write this post. However, it’s been my experience that, even in 2019, Piaget and his stage theory are still cited and referred to, both implicitly and explicitly, by administrators, PD “gurus”, and teachers alike as an indisputable truth about how children learn and develop.

Vygotsky, like Piaget, is another of the small number of theorists that are well-known amongst teachers, and his zone of proximal development (ZPD) seems to me to be one of the least understood, yet most often cited concepts in education (probably only second to teachers mistaking negative reinforcement for positive punishment). That we still refer to the ZPD is not necessarily a bad thing per se, it’s just that it’s problematic in that:

- It’s a developmental theory, not a short-term instructional strategy (Smagorinsky, 2018), and as I’ve just explained, our current understanding of cognitive development has changed.

- When teachers and trainers say ZPD they’re probably referring either to the “Goldilocks principle” (Katz, 1985) or scaffolding (Chaiklin, 2003; Smagorinsky, 2018), in which the latter is not a hypothetical developmental model, but an empirically tested instructional strategy (Rosenshine, 2012).

- Newer empirical work on said scaffolding, as well as newer research in cognitive science that has implications for instruction should be much more prominent in teacher knowledge, training, and professional conversations than work that was done decades ago.

Here’s what Chaiklin (2003) has to say on the matter of the ZPD:

Now that more of Vygotsky’s texts are readily available, there is no excuse to continue to use limited or distorted interpretations of the concept. It seems more appropriate to use the term zone of proximal development to refer to the phenomenon that Vygotsky was writing about, and find other terms (e.g., assisted instruction, scaffolding) to refer to practices like teaching a specific subject- matter concept, skill, and so forth. This is not to deny the meaningfulness of other investigations (e.g., joint problem solving, dynamic assessment of intellectual capabilities), only to indicate that there is no additional scientific value to refer to this as zone of proximal development, unless one concurrently has a developmental theory to which these assessments can be related. It is precisely on this point that one can see, by way of contrast, how most work that refers to zone of proximal development does not have such a developmental theory, even implicitly.

A way forward…

As I mentioned in a recent podcast, it’s important to me that we start taking professional learning in education more seriously. One way forward is to build teachers’ research literacy (Evans, Waring, & Christodoulou, 2017). Schools should put peer-reviewed articles at the center of teacher workshops and staff meetings, as well as offer training in research skills to their teachers and administrators. Schools should pay for access to a research database, and train and expect teachers to use it. Schools should also put someone in charge of leading research-informed discussions in their schools, including teacher book clubs and evidence-based professional learning communities.

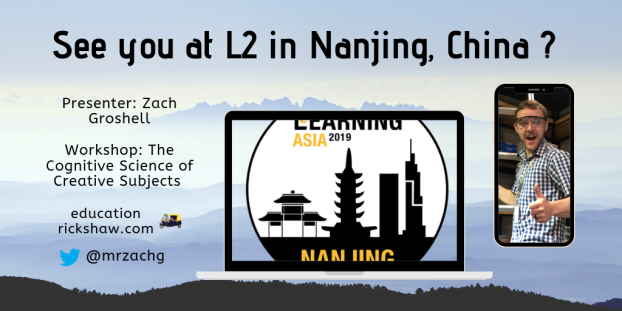

A related step to ameliorating how we do teacher education is to actually teach teachers the basic science of learning. Willingham (2018) suggests that teacher preparation programs focus on translating relevant scientific principles into classroom applications, as perhaps not everything that is of importance to cognitive scientists is necessary for teachers to know. This is why I’ve decided to put together a workshop, to be presented at Learning2 Asia in Nanjing, China, on principles and classroom applications of cognitive science. Participants will conduct a series of experiments on themselves to test various principles that have been found in the past twenty years of cognitive science, all relating to creativity and design. These include concepts such as the basics of working memory (i.e Harrison et al., 2013), cognitive load (Sweller, 2019), multitasking (Adler & Benbunan-Fich, 2012), and expertise (Ericsson, 2015).

Let’s move beyond the contents of Psychology 101. Let’s move beyond the low, low expectations that we have for preservice teachers that leads to the memorization of only a handful of 20th century theorists and their associated theories in time for the Praxis II exam. Let’s develop a profession that is engaged and fluent in the discoveries that learning scientists are making right now.

I hope you enjoyed this post. If you have the means I’d love to see you over in Nanjing for Learning2 Asia 2019. Click here for more info. Let’s talk learning!

References

Adler, R. F., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2012). Juggling on a high wire: Multitasking effects on performance. International Journal of Human Computer Studies, 70(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2011.10.003

American Psychological Association. (2015). Top 20 principles from psychology for Pre K – 12 teaching and learning: Coalition for Psychology in Schools and Education. American Psychological Association, 1–38.

Chaiklin, S. (2003). The zone of proximal development in Vygotsky’s analysis of learning and instruction, 1–21.

Ericsson, A. K. (2015). The Differential Influence of Experience, Practice, and Deliberate Practice on the Development of Superior Individual Performance of Experts. Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance.

Evans, C., Waring, M., & Christodoulou, A. (2017). Building teachers’ research literacy: integrating practice and research. Research Papers in Education, 32(4), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1322357

Harrison, T. L., Shipstead, Z., Hicks, K. L., Hambrick, D. Z., Redick, T. S., & Engle, R. W. (2013). Working Memory Training May Increase Working Memory Capacity but Not Fluid Intelligence. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2409–2419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613492984

Katz, Lilian G (01/01/1985). “A Framework for Research on Teacher Education Programs”. Journal of Teacher Education , 36 (6), p. 9.

Macdonald, K., Germine, L., Anderson, A., Christodoulou, J., & McGrath, L. M. (2017). Dispelling the myth: Training in education or neuroscience decreases but does not eliminate beliefs in neuromyths. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(AUG), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01314

Martinez, M. E. (2010). Learning and cognition: The Design of the Mind. Upper Saddle River, NJ [u.a.]: Merrill.

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of Instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00507.x

Siegler, R. S. (2000). The rebirth of children’s learning. Child Development, 71(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00115

Smagorinsky, P. (2018). Is Instructional Scaffolding Actually Vygotskian, and Why Should It Matter to Literacy Teachers? Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 62(3), 253–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.756

Sweller, J. (2019). Cognitive load theory and educational technology. Educational Technology Research and Development, (0123456789). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09701-3

Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2010). The gap between educational research and practice: Views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902919257

Willingham, D. T. (2018). Unlocking the science of how kids think. Education Next, (Summer), 42–49.

True and mindful analysis. KP Education department in Pakistan went one step further by declaring that half of the teachers here were unable to teach some basic language skills influentially, faced the same reactions. Thanks for realizing , guidance and recommendations. Zafar

LikeLike

Sounds good, but you’ve left out the date, contact details and costs of the workshop. It’s hard for me to send this to my PYP coordinator without that info. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Added, thanks Felicity!

https://learning2asia.org/project/zach-groshell/

LikeLike

Or even better, lets have teachers not know the names of any theorists, but rather know a handful of particularly useful theories and how to use them 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought about that, but I find the names of researchers important when following a research trail I.e mining the reference section of an article I find. The important thing is that we don’t learn names just to be able to build an argument from authority, aka Dewey said it, so it must be true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I used to study experimental psychology when I was young. The science of psychology is pretty much dead, subsumed under neuroscience and marketing programs.

LikeLike