The phrase “chasing the dragon” refers to the classic cycle of addiction. People keep chasing the dragon not because it’s working, but because they’re convinced the payoff will eventually come — if only they keep trying.

(I’ll spare you a digression into my history with the game of golf.)

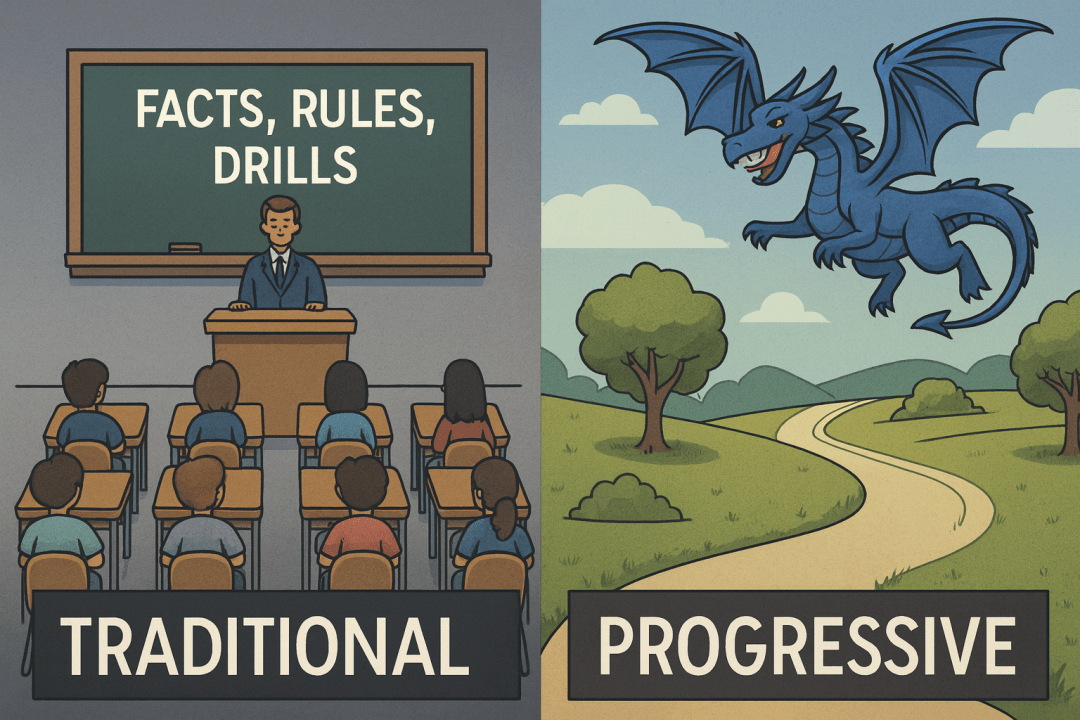

Teachers are told to chase the Discovery Dragon. As the image below illustrates, “teaching stuff effectively” is never enough. The message is that “real” teaching requires MORE— more inquiry, more student-led exploration, more open-ended tasks, more ceding of control to learners.

And part of what makes the Discovery Dragon so elusive is that its form keeps changing: one year it’s “inquiry,” the next “constructivism,” then “student agency,” then “project-based” – all just “discovery learning” again under a new name. And if you fail to be “progressive” enough, you’re cast as a dinosaur stuck at the bottom of the mountain: a low-level traditionalist who hasn’t ascended to the enlightened heights of innovation.

The Discovery Dragon becomes the shimmering prize at the summit — always just out of reach, continuously rebranded, never “done right” or implemented properly. And our evaluation tools reinforce this fantasy. You can be “Proficient” using explicit instruction, sure. But if you want to be “Distinguished”? Then the students had better be teaching each other when I pop in!

All of this is damaging because it simply doesn’t work. Students learn extremely well with structured, explicit teaching. And there isn’t just one reason for this, there are several. Most obviously, everything a student must learn must be attended to and thought about. Thirty children “collaborating” generates a litany of transactional costs even in the most well-behaved classrooms. Noise impedes learning; social dynamics pull attention away from ideas. The only person with the authority and responsibility to regulate the environment so it becomes conducive to focus, effort, and intellectual work is the teacher. Unsurprisingly, many students prefer messing around with friends over doing work, especially when the teacher’s capacity to monitor is split.

But it doesn’t stop there. Everything a student attends to becomes something they must work with in mind, and working memory is brutally limited. Beginners are overloaded by information that feels trivial to experts. Our own subject expertise blinds us as teachers: we underestimate the burden of novel steps, unfamiliar language, and under-practiced material for kids when they’re just learning a topic. That is exactly why teaching must be incremental, systematic, and carefully engineered. The idea that students should “pick up a book and figure out the squiggles” now sounds laughable in the era of Sold a Story and the Science of Reading, but advocates of the Discovery Dragon want teachers to apply that same logic to math, science, writing, and history. It’s absurd and it’s beneath us.

I feel for teachers. I was one of the ones pulled into the intoxicating promise of inquiry-based, discovery-based, minimally guided instruction. And just like countless others, I watched students fail to learn much of anything. Digging into the science of learning was clarifying – almost therapeutic – but it mostly confirmed what common sense had been whispering all along: How can I expect children to construct upon shaky foundations? How can I assume they won’t harden misconceptions if I ask them to “figure it out”? How will they ever get good at anything without systematically designed practice and corrective feedback — the kind unserious people sneer at as “drill and kill”? Why wouldn’t I start with the end in mind, teach in focused, manageable chunks, and check relentlessly that students are learning before adding the next step?

We don’t need to chase dragons. We need to teach. This job is not a quest for mystical enlightenment – it’s the disciplined work of designing a sequence of moments that leads to powerful, lasting, enabling knowledge and skills for all students. It’s the deliberate engineering of success so students feel the thrill of genuine progress. The future belongs to the teacher who embraces the science of how kids learn, not the one chasing the Discovery Dragon up a mountain to nowhere.

Discover more from Education Rickshaw

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.