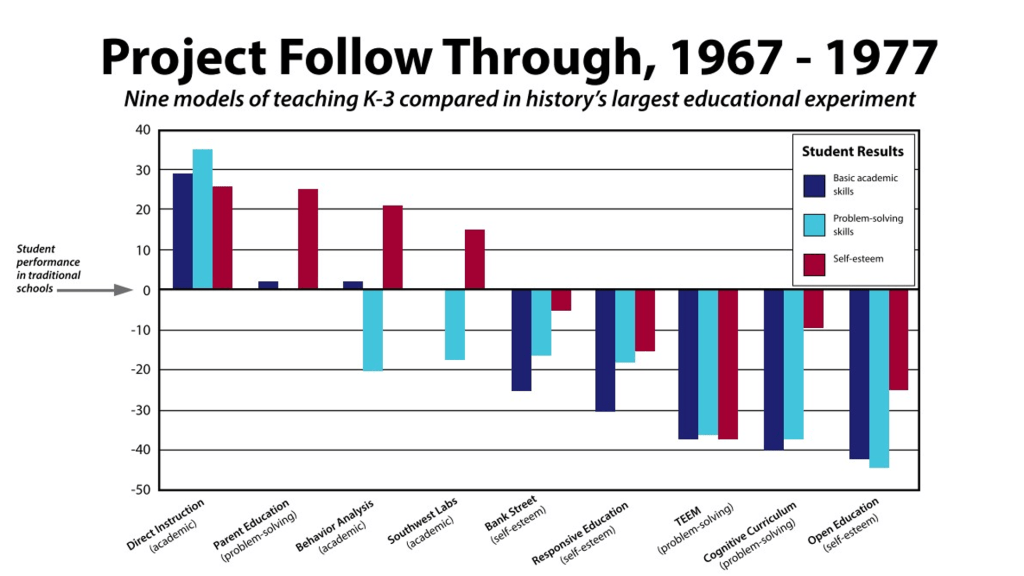

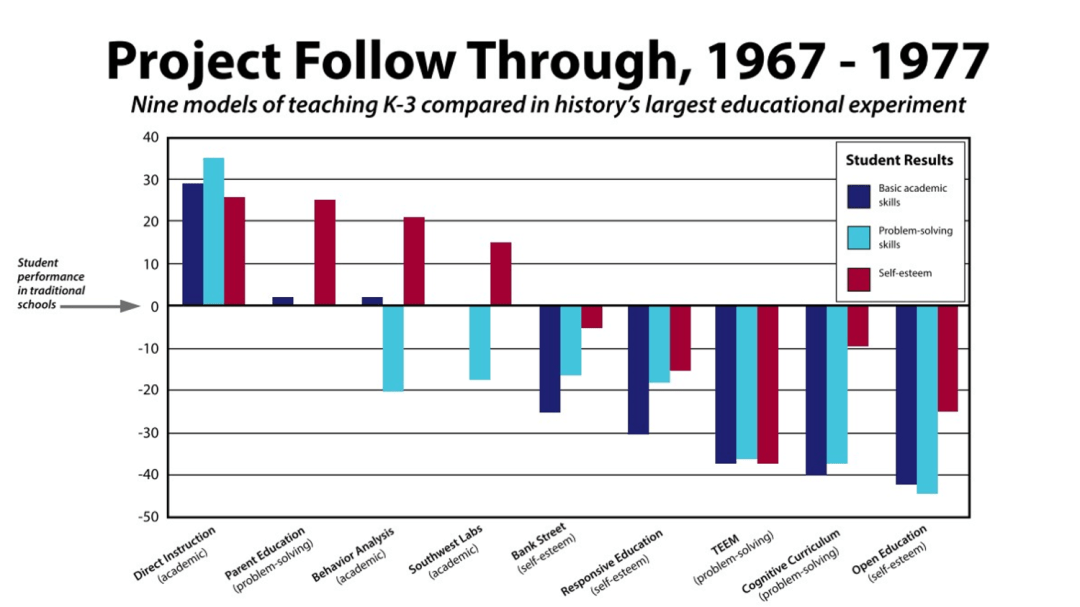

People often ask me to talk about Project Follow Through, a landmark federally funded study that compared major approaches to teaching young children at scale. They tell me they enjoy hearing my take on it, and I’m always glad to share what I’ve learned.

In his new Substack, Doug Carnine pointed readers to a classic paper on Project Follow Through. I’d read it a while ago while prepping a podcast episode, but revisiting it reminded me of something we often gloss over: Direct Instruction’s Follow Through results weren’t just attributable to “good teaching moves” or strong “delivery.”

What the DI team brought to Follow Through was a full model—philosophy, curriculum, assessment, training, coaching, and monitoring—engineered to work together. Put differently, DI’s outcomes didn’t come simply from being “explicit”; they came from a system designed to make mastery all but guaranteed.

Delivery mattered—but it wasn’t the whole story.

Here are some of the things I think we neglect to mention when it comes to the genius that was the Direct Instruction Follow Through Model.

A carefully designed, sequenced curriculum

The Direct Instruction Follow Through Model centered on programmed lessons crafted through extremely careful instructional design rather than teacher-made lessons. The programs were organized into levels, with daily lessons built around “tracks” that introduced material incrementally and gradually increased in complexity while fading support. The sequence wasn’t based on coverage and exposure, but on mastery principles that incorporated spacing, interleaving, retrieval practice, and cognitive load theory—well before those terms became part of our everyday vernacular.

It’s important not to shortchange this aspect of DI, as the casual observer of Follow Through often does, because—as you’ll see shortly—the programs enabled, to a great degree, the other components of the model.

Homogeneous instructional grouping

In Direct Instruction’s Follow Through implementation, teachers and supervisors were trained to administer placement tests into the programs so that they could create homogeneous instructional groups and build flexible schedules. This made it possible for students to build on what they already knew—step by step—and ensured that students who needed to catch up could be monitored closely and given more intensive support.

Classroom organization and use of trained aides

The Direct Instruction Follow Through Model increased interactive teaching time by running small-group instruction in the early levels. It made that possible at scale by training aides (i.e., paraeducators) to function as teachers, not just helpers—so more groups could be taught, more often, in the core areas, with higher time on task and opportunity to respond than would otherwise be possible.

Reinforcement and motivation systems

The motivational model of the Direct Instruction Follow Through Model combined frequent, immediate positive reinforcement (including the teacher–student “game,” an innovation I still use today) with consistently high success rates. Those success rates were only possible because, again, students were accurately placed into well-designed programs—so they weren’t routinely asked to “struggle” through work that was way over their heads.

Thorough implementation support: training and instructional coaching

The Direct Instruction Follow Through Model treated implementation as a system: training, deliberate practice with feedback, and frequent in-class support. In many respects, they were doing instructional coaching long before “coaching” became trendy in education. As DI expert Marcy Stein likes to tell me, what made this coaching different from many contemporary forms is that it was possible largely because coaching was embedded in the implementation of an effective program.

Principal and supervisory roles

In the Direct Instruction Follow Through Model, principals and supervisors had defined responsibilities for protecting instructional time and ensuring the programs were implemented as intended, and they spent substantial time in classrooms supporting instruction. The model specified ratios (roughly one supervisor for 10–15 classrooms) and emphasized that supervisors spend most of their time in classrooms supporting instruction.

Frequent progress monitoring and data-driven instructional decisions

The Direct Instruction Follow Through Model tracked daily exercises and mastery tests to ensure learning was actually happening. The monitoring system was tied to actions: reteach skills, adjust pacing, regroup students, or address teacher performance deficits (verified through classroom observation). In today’s language, they were basically running MTSS before MTSS was a thing.

Manualized procedures beyond lessons

The Direct Instruction Follow Through Model included manuals not just for teachers but also for supervisors, administrators, and parents—standardizing the broader implementation environment. Parents often served as aides or parent workers, with concrete responsibilities (supporting instruction, reducing absenteeism, connecting families to services, coordinating parent structures).

Conclusion

Because Follow Through evaluated whole instructional models as they were actually implemented, it tells us with unusual clarity that Direct Instruction outperformed the alternatives in that real-world package.

What it can’t do—by design—is isolate which specific components of that package were most responsible for the advantage. Was it the meticulous design of the curriculum materials? The placement testing and homogeneous grouping? The relentless monitoring and data-based decision making? The increased interactive teaching time? The scripts, choral responses, and built-in correction routines?

Which were essential and which were incidental to its success?

As I’ve gone from school to school—many of them successful, and others less so—I’ve become less convinced that there’s a single “secret sauce” responsible for results. What keeps standing out instead is cohesion: each component—curriculum, delivery, coaching, monitoring, and implementation support – designed to strengthen the others, so the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

And, in a slightly related way, it’s why Carnine’s broader point about restructuring in education hits home: stop “touching only a part of the education elephant” and re-build the full system so the pieces reinforce one another.

Discover more from Education Rickshaw

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.