I was recently invited to debate the utility of “pre-testing” or pre-questions as an instructional strategy in a new webinar with my friends at InnerDrive (link here). I wish I had prepared and performed better, but it turned out to be good fun anyway. Below is the recording, as well as some lingering thoughts about pre-testing.

Imagine I ran several experiments in which I randomized participants into two groups. In each experiment, one group received more instruction than the other. Would you be surprised that, on average, the participants who received additional instruction learned more than those with less instruction?

Probably not. In fact, we could probably predict that no matter what instructional technique I used as additional instruction—even giving students instruction tailored to their preferred learning styles—the students with the additional instruction would do better than those without it. They simply received more opportunity to develop their skills.

This phenomenon was drilled into me in my methodology courses in college: if a teaching practice is said to work, always ask, “compared to what?”

Let’s apply this concept to one of the strongest empirical findings in learning science: retrieval practice. Also known as the testing effect, the finding suggests that having students recall knowledge after studying a text or undergoing a lesson is highly effective for learning.

But here’s the thing: the testing effect is a strong and compelling finding because of its comparison group. In testing effect studies, both groups study the same lesson, but in the next phase, one group is prompted to restudy the text while the other is given a series of recall questions about the text. This sets up a passive (restudy) and active (testing) condition in which both groups get equal opportunity to learn, but testing almost always comes out as the superior technique. Researchers can then run more experiments with different comparison conditions, such as concept mapping versus testing, to see if the testing effect holds. The point is, we’d be getting ahead of ourselves if all it took to establish a testing effect was to compare groups of kids who got recall questions with those who got nothing. Something is always better than nothing.

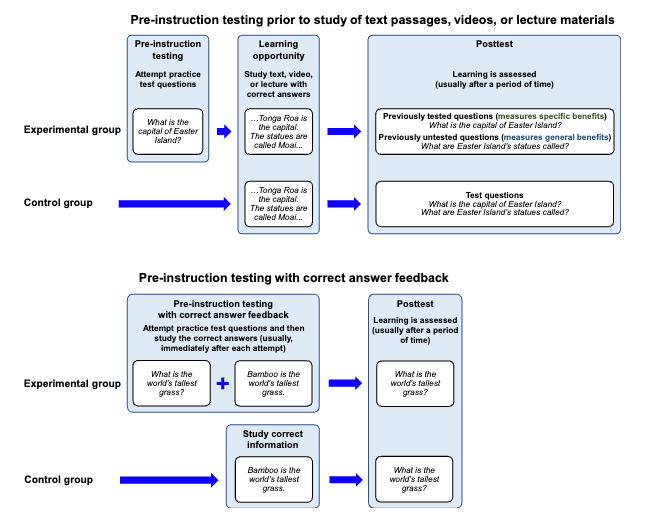

Which brings us to the (relatively) new but promising finding in learning science research: the pre-testing effect. In pre-testing studies, students are asked questions about knowledge they do not know before being taught the material. You might think that to establish a pre-testing effect, the long-standing research design from the testing effect literature would simply be flipped: one group would receive pre-questions while the other is given “pre-study” factual statements. For example:

- Pre-Testing Group: How many families originally landed on Rapa Nui?

- Pre-Study Group: One family originally landed on Rapa Nui.

In the first group, students would take a stab at the question in the provided box, while in the second group students would simply be prompted to read the question formatted as a statement.

Now, this should be the bare minimum for a research program that investigates pre-testing, but the vast majority of papers compare pre-testing to… nothing! See the long blue arrow.

Beyond concerns about research designs, there are a number of reasons to be skeptical of pre-testing. For one, it asks students to make a guess that could lead them to remember that guess instead of the actual answer. In a classroom full of real children, this is especially worrisome, because unless the pre-testing happens in silence, students will be exposed to their peers’ incorrect answers. What we think about is what we remember.

It is also important to consider the opportunity cost of pre-testing. Is guesswork really the best use of a student’s time, when that time could instead be devoted to an additional retrieval opportunity at the end of the lesson? Retrieval practice is a strongly supported strategy, while evidence for pre-testing is weaker, so within the same time frame teachers are better served by placing questions after instruction rather than before it. And what about embedding questions during the lesson, immediately after new material is introduced? This approach strengthens the link between question and answer, instead of separating them in an artificial pre-testing phase designed more for research than from sound instructional principles.

And that brings us to motivation (for an interesting discussion on this, see Pan & Carpenter, 2023). Is the best way to start a lesson really to confront students with a moment of failure? Do students in a real classroom sustain their effort on low-success questions once the novelty of “take a wild guess” wears off? In the messy reality of classrooms, it’s reasonable to question whether low-success pre-retrieval questions end up taking more time than high-success retrieval questions (efficiency), draining energy from the room (motivation), and privileging the knowledge of the highest-performing and most confident students (equity). Why not begin a lesson with high success questions and examples that connect to what students already know? This is usually called “activating prior knowledge.”

Given these considerations, we should be cautious about encouraging pre-testing until we have collected enough data comparing it to conventional, tried-and-tested instructional techniques. Any pre-testing study that fails to compare pre-testing with pre-studying, pre-testing with post-testing (retrieval), pre-testing with embedded testing, or with any number of prior knowledge activation techniques does little more than demonstrate the obvious: more instruction is more effective than less. This is especially relevant given that pre-testing effects tend to be vanishingly small.

I actually think in a battle between the pre-testing versus pre-studying formats for “Rapa Nui” that I outlined above, pre-testing would win. Putting a box in the learning software that the student has to fill in requires action, thereby increasing attention on the information. The fact that they are questions gives students practice with a variation of how items will appear on the test at the end of the experiment. Plus, the comparison format here for pre-studying is a bizarre instructional exercise (e.g., hey guys, read these facts one at a time) that no teacher would ever use in a realistic setting.

To make a truly meaningful comparison, I recommend the following research design be applied to future pre-testing studies:

- Pre-Testing Group: How many families originally landed on Rapa Nui?

Box

- Pre-Study Group: One family originally landed on Rapa Nui. (Disappears)

How many families originally landed on Rapa Nui?

Box

In this design, both groups have the chance to fill in the blank, with the pre-studying group being given the correct answer and asked to repeat it back. This approximates the use of choral response in an explicit teaching lesson and actually gets at the question teachers want to know: does pre-teaching the facts ahead of instruction improve learning compared to asking students to guess?

References

Pan, S. C., & Carpenter, S. K. (2023). Prequestioning and pretesting effects: A review of empirical research, theoretical perspectives, and implications for educational practice.

Richland, L. E., Kornell, N., & Kao, L. S. (2009). The pretesting effect: Do unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016496

Discover more from Education Rickshaw

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.