Like millions of people around the globe right now, I am practicing social distancing. One valid point that has been brought up online is that the term should really be physical distancing rather than social distancing; Of course self-isolation and quarantine separate us geographically, but the psychological space between us doesn’t have to be so vast. These days we have online tools that can connect us socially in ways that can mitigate the loneliness that comes with physical separation.

In the field of instructional design for online learning, this is not a new concept. Transactional distance theory (TDT, Moore, 1996) is a useful theory for online course design that proposes that the distance during instruction is transactional, not spatial or temporal (Gorsky & Caspi, 2005; Saba & Shearer, 2017). TDT suggests that if we work to reduce the psychological space between participants and instructors through pedagogy, it will likely lead to higher learning outcomes.

While traditional TDT includes additional components that can be used to reduce transactional distance between learners and their instructors, I think all teachers teaching online during the Coronavirus online learning period should pay particularly close attention to the TDT’s core constructs of dialogue and structure.

Dialogue

A good online teacher facilitates a variety of forms of interaction between participants and instructors, such as instructor-learner and learner-learner interactions (Huang, Chandra, DePaolo, & Simmons, 2016). Even though online students are not in the physical classroom to engage in discussions, teachers should use the discussion and collaborative tools in their learning management system to increase dialogue and interaction. Teachers should update their profile pictures, post video greetings, and stimulate dialogue between students through the use of written, audio, and video comments. I recommend checking out this older post about the advantages to using online tools to elicit student responses over raise your hand in physical classrooms.

Structure

Structure refers to the level of guidance and direction provided within the course design, as well as the level of responsiveness of the course design to accommodate individual learners’ needs (Huang et al., 2016). A rigid course structure may disrupt organic and creative dialogue, but novice learners dealing with novel information may require higher levels of structure than experts (Benson & Samarawickrema, 2009; Huang et al., 2016).

Teachers should attend to the complex relationship between structure and dialogue (Saba & Shearer, 2017) in order to reduce transactional distance. We can measure how transactional distance is perceived by students in their courses by surveying them (Elyakim et al., 2019). Recent efforts by researchers (Benson & Samarawickrema, 2009; Huang et al., 2016) have revealed that courses with high structure and high dialogue (+D+S) tend to be the most effective in reducing transactional distance and that courses with low dialogue and low structure (-D-S) will likely result in the most transactional distance, with +D-S and -D+S falling somewhere in the middle.

Synchronous vs. asynchronous learning

One of the weirdest debates (to me, at least) that has raged in education as we wait for our schools to reopen is over whether we should be focusing our efforts on delivering synchronous or asynchronous learning experiences, as if this was an either/or decision. Fueling the debate are teachers reporting Zoom and MS Teams horror stories on Facebook and Twitter, and parents, like in the video below, who are so frustrated by course designs that they are just about ready to give up on distance learning altogether.

The thing is, there is nothing inherently wrong with asynchronous learning, nor with synchronous learning. Each is suited to solve different instructional problems, under specific conditions, depending on the goal of the learning, the characteristics of the learners, and the course format. Now, don’t get me wrong, when I hear of school leaders prescribing 100% synchronous learning during this time period, I can’t help but cringe. Besides synchronous learning tools being notoriously unreliable and difficult to use with a large number of young students, prescribing 100% synchronous learning violates two key principles of instructional design for online learning:

- A direct copy of a face-to-face classroom using online tools will surely fail

- You should never completely eliminate a useful instructional strategy from your toolbox

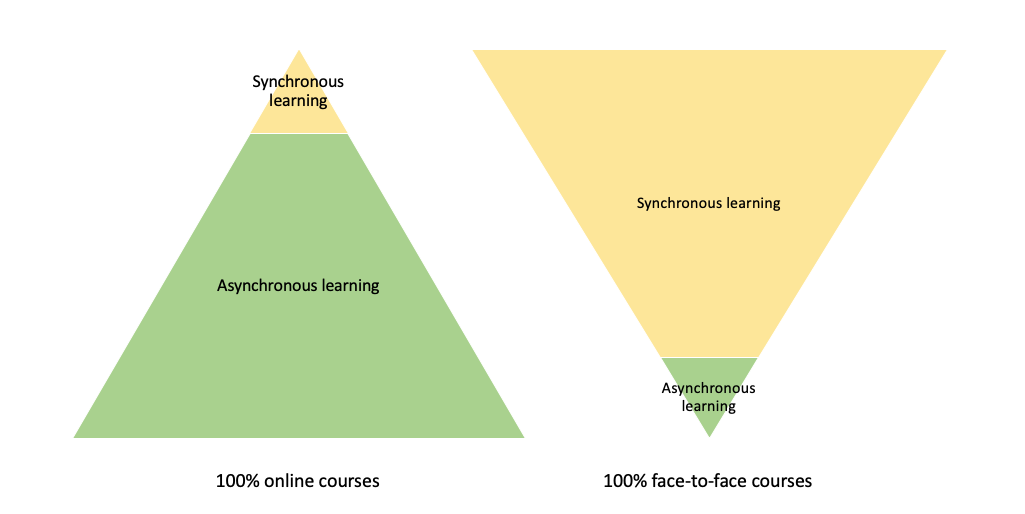

While it works much, much better for the learning context that we’re in at the moment, we probably shouldn’t prescribe a 100% asynchronous format for an online course either. Students can benefit from a synchronous dialogue session via conference call once in a while, if only to reduce the feeling of isolation between peers and instructors. For what it’s worth, if I had to depict my own views about when to use synchronous or asynchronous learning as a graphic, it would look something like this:

Instead of having an unproductive debate over asynchronous or synchronous learning, one way we can improve our practice during these unusual circumstances is by attending to the design components of dialogue and structure, as proposed by transactional distance theory and other online learning theories, to reduce transactional distance and improve learning outcomes. While we may have to continue this physical distancing for some time, when teachers design well-structured courses that enable students to ask questions, engage in discussions, receive and give feedback, and actively participate in class activities (Joksimović, et al., 2015), we bring our learning communities closer together.

– Zach Groshell

References

Benson, R., & Samarawickrema, G. (2009). Addressing the context of e-learning: Using transactional distance theory to inform design. Distance Education, 30(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910902845972

Elyakim, N., Reychav, I., Offir, B., & McHaney, R. (2019). Perceptions of Transactional Distance in Blended Learning Using Location-Based Mobile Devices. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(1), 131–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117746169

Gorsky, P., & Caspi, A. (2005). A critical analysis of transactional distance theory. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(1), 1–11.

Huang, X., Chandra, A., DePaolo, C. A., & Simmons, L. L. (2016). Understanding transactional distance in web-based learning environments: An empirical study. British Journal of Educational Technology<

Joksimović, S., Gašević, D., Kovanović, V., Riecke, B. E., & Hatala, M. (2015). Social presence in online discussions as a process predictor of academic performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learn

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view, Belmont, CA: Wad- sworth

Saba, F., & Shearer, R. L. (2017). Transactional Distance and Adaptive Learning : Planning for the Future of Higher Education. Milton, UNITED KINGDOM: Routledge. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/capella/detail.action?docID=5107319

Thanks for citing! – Zach

LikeLike

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning….

LikeLike

Thanks for the reboot, Pedro 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yw!

LikeLike

Thanks for linking! – Zach

LikeLike

The current situation now make more people to active in online platform. And why not online learning now play an important role to our edu system to continue educating students. As per synchronous concern, somehow most of the school are ready to adopt this system of learning. Thank you..

LikeLike

We can use Synchronous learning to stay on task for the whole school year’s curriculum. However, we can implement Asynchronous learning for a more student centered approach. Although asynchronous learning might have more benefit for each student, it is in reality it is not practical to cater to a vast majority for students efficiently in this manner. Using remote learning, we instructors can implement synchronous learning throughout the year just to make sure that the content that needs to be covered will be met and we can use asynchronous learning by directly communicating with students that may be falling behind to give them the individual care that they need to keep up with the rest of the class. This is actually hard to achieve without remote learning, because in reality setting up an appointment to meet with each student indvidually will take up too much time. However remote learning gives us unlimited access to students and vice versa.

LikeLike

One possible solution is to separate the course provider and the tutor. An asynchronous online course together with private tutor support in a synchronous manner. That way the course can be entirely automated, with everyone being given the chance to assist each other in a synchronous manner. Then people “teaching” don’t have to have the knowledge (you can just look this up on the course materials), they just have to act as a guide.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the contribution. I think there are a lot of ways we can make this better

LikeLike